Greetings and salutations!

In this edition of the newsletter, we’ll dig into what makes practice meaningful — not the rote, mindless repetitions we’re sometimes told to endure, but authentic, well-structured sessions that move us closer to genuine understanding and skill.

Whether you’re a teacher, coach, or simply striving to improve at something important to you, we will cover a few different parts:

- The point of practice

- Characteristics and challenge for practice

- Organizing tasks in a practice session

Consider this an invitation to be a little more curious, a little more experimental, and perhaps to find new energy in how you help others (or yourself) improve. Ready to step into learning with more intention and resilience? Let’s get started with practice!

Ideas

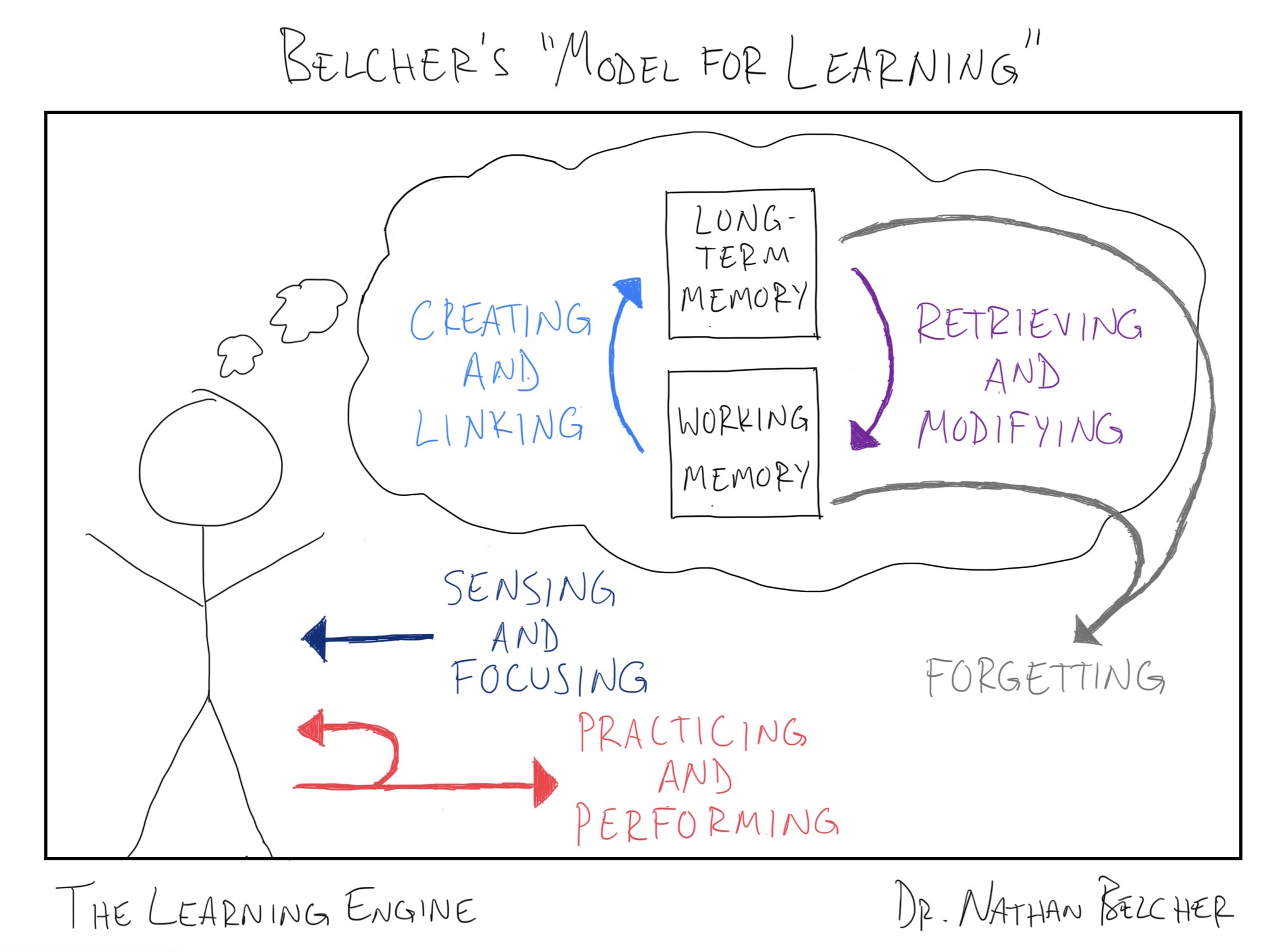

Before we get into the specifics of practice, take a minute and review my Model for Learning. Please work yourself through the image, remembering specifics for each part and the connections in the model.

[For a much deeper explanation on the process of learning, check out this essay: That’s How Learning Works?!?! A Comprehensive Model for Understanding the Learning Process.]

The Point of Practice

The output for Belcher’s Model for Learning is called Purposeful Application, which includes practice and performance. Though both are included in Purposeful Application, the point of practice and performance are different.

The point of practice is to learn:

- What do we think we know and can do?

- What do we actually know and can do?

By purposefully applying the sets of knowledge and skills in our conceptual models, we can compare the answers to those two questions. If the answers to the questions match, then great! — we are ready to move to the next level through more challenge. If the answers to the questions are different, then we gain a valuable insight into a weakness for our knowledge and skills — which gives us a way to focus and continue improving.

[The next newsletter will focus on performance, so I’ll explain the point for performance in that newsletter!]

Characteristics and Challenge for Practice

Both practice and performance have specific roles to play in learning; to differentiate between their roles, I’ve created a spectrum of practice and performance.

I define Practice with these main characteristics:

- Closed and controlled environment

- Structured sequence and complexity of tasks

- Focused on the knowledge and skills in a single conceptual model (or small number of conceptual models)

By focusing on a single conceptual model with a structured sequence and complexity of tasks in a controlled environment, the learner can receive useful feedback from the task or instructor — and apply that feedback during the next task.

Changing the Challenge

Every task in a practice session has a sweet spot for learning — this sweet spot comes from the amount of challenge in the task.

Assuming that the learner is engaged with the task and giving a strong effort, the goal is roughly an 80% success rate — so success on roughly 4 out of every 5 repetitions of the task. If the learner is at a 100% success rate then increase the challenge; without enough challenge, there is a risk of losing focus and becoming bored. If the learner is less than 50% then decrease the challenge; with a low success rate, there is a risk of losing motivation to continue learning.

There are a few different ways to change the challenge (and intensity) for a task.

- Stakes for the outcome: What happens for success or failure?

- Difficulty of task: How easily can the learner complete the task?

- Time pressure: What happens if the amount of time to complete the task changes?

Using the challenge and intensity in each task pushes the learner into the sweet spot for learning. This allows the learner to modify, connect, and organize the knowledge and skills in their conceptual models — which is the very definition for learning!

Organizing Tasks in a Practice Session

Each practice session has some tasks; the tasks should be organized for the level and personal characteristics of the learner.

There are several ways to organize the timing for tasks:

- Blocking — Complete the same task for an extended amount of time (A / A / A / A)

- Spacing — Repeat a task with some amount of time between the repetitions (A / _ / _ / A)

- Interleaving — Combine the repetitions for a few different tasks (A / B / C / A / B / C)

Blocking should be used sparingly; repeating the same task makes the learner better at the task in that moment, but offers little long-term learning.

Combining spacing and interleaving — especially with related tasks — is a much better way to organize tasks. This combination makes the learner pay attention during each repetition of the task, plus forces the learner to constantly remember the knowledge and skills for different tasks. Though the learner may feel they are not learning very well during this combination, pushing through the experience produces strong long-term learning.

There are also two other ways to implement each task:

- Randomizing — Changing the order of tasks in a random way

- Retrieving — Deliberately thinking about the knowledge and skills in a task before doing the task

Randomizing can be combined with spacing and interleaving, increasing the challenge and intensity. Randomizing is a useful way to get into the “Practice the Performance” level of practice; performances are in an open and complex environment (which includes a more random order of events), so using randomization in practice helps prepare learners for performances.

Retrieving is a special part of practice that can be used for every task. By deliberately thinking about the knowledge and skills in a task before doing the task, the learner is primed to focus on the knowledge and skills. This priming makes the learner more aware of the point of the task, helping them know how to confirm or modify their knowledge and skills.

[If you want more information on practice (with drawings and examples!), check out this essay: The Fundamentals of Practice — Maximizing Learning with High-Impact Types of Practice.]

Using spacing, interleaving, randomizing, and retrieving keeps the learner engaged with each task, creating focus in the practice session. Through their focus and the design of tasks, practice is efficient and effective — helping the learner progress more quickly with their knowledge and skills!

Stories

I’ve used practice throughout my life; here are a couple of stories.

Story 1: One example comes from my work as a physics teacher. Early in my career, I gave sets of practice problems — but did not focus on the sequence or complexity for each set of practice problems. This created issues because some problems were very easy whereas other problems were very challenging; although there could be a slight benefit from this mixture of problems, student became frustrated because they did not know what they were getting from each problem. As I progressed in my career, I became much better at creating problems sets that built from easy to hard. Students had a clear picture of the “level” for each problem, which gave them confidence as they successfully completed problems for each level. In addition, students could pick and choose their own problems — giving them autonomy and choice, which allowed students to take control of their learning. I believe that constructing sets of problems with a clear progression helped the students learn more efficiently and effectively, setting students up for success on future assignments.

Story 2: Another example is from my golf practice. I’ve been practicing my ability to hit the ball with different shapes and heights, which is a challenging skill. I use the ideas of spacing, interleaving, randomizing, and retrieving for my practice set, forcing myself to stay uncomfortable and push myself through any frustration. Even with all my knowledge about practice, performance, and learning in general, I still have to put in the work — pushing myself outside of my comfort zone and giving maximum effort. Some days are really tough, especially with certain clubs and certain shots; however, I’ve seen real growth in my ability during the last couple months, so I know the plan is working!

Questions

- What do you think about the ideas for the point of practice?

- How do you define practice?

- What ways have you changed the challenge and intensity in your practice?

- What ways have you used spacing, interleaving, randomizing, and retrieving in your practice?

- How can you create a practice session for yourself or a learner?

Learning happens when we share what we are thinking, so I would love to hear your answers! Also, you can use these questions as conversations starters with friends and family — hearing their answers and having a conversation would be great!

[Note — Some of the ideas in this newsletter come from these sources: K. Anders Ericsson’s deliberate practice; Robert and Elizabeth Bjork’s desirable difficulties; and, Lev Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development. If you want more details on the sources or other ideas, please respond to this newsletter!]

If this newsletter resonated with you, please share on the socials and with someone who you think would also benefit; I would greatly appreciate any help in spreading these ideas!

Thanks for reading this newsletter — and all the best!

Nathan